At the Forest’s Edge: New Research Uncovers How Microbes Shape Ecosystem Resilience

Microbes are everywhere – on your skin, in your gut, in the soil beneath your feet, even floating in the air you breathe. Most people think of microbes in simple terms: some make you sick, while others help keep you healthy. But microbes’ influence stretches far beyond human bodies. These astonishingly complex organisms regulate the health of forests, oceans, and grasslands, and determine how ecosystems respond to environmental change.

Microbes are everywhere – on your skin, in your gut, in the soil beneath your feet, even floating in the air you breathe. Most people think of microbes in simple terms: some make you sick, while others help keep you healthy. But microbes’ influence stretches far beyond human bodies. These astonishingly complex organisms regulate the health of forests, oceans, and grasslands, and determine how ecosystems respond to environmental change.

So what exactly is a microbe?

Microbes include bacteria, archaea, fungi, and protists. Bacteria are single-celled organisms that help recycle nutrients and foster beneficial interactions between plants and animals. Fungi can be single-celled, like yeast, or made of many cells, like molds, and they help decompose dead material and support plant growth. Protists, like algae, also help recycle nutrients and produce oxygen through photosynthesis.

Together, these tiny organisms have a critical role in sustaining life on Earth.

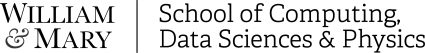

Geoffrey Zahn, Assistant Professor in Applied Science, is the principal investigator of the TIDAL Lab (Translational Insights into microbial Diversity, Assembly, & Linkages), which focuses on understanding microbial communities and their roles in the environment. The lab’s research spans diverse ecosystems, from oceans to endangered prairies, and aims to better predict how microbial communities assemble, respond to environmental change, and what consequences this implies for global ecosystems.

“Sometimes we are analyzing DNA from the stratosphere to track intercontinental microbial movements, sometimes we are trying to design probiotic microbiomes to aid in conservation efforts, and sometimes we are simply aiming to describe and characterize new species with unique or valuable ecological functions,” said Zahn.

The Edge Effect

For decades scientists have noticed that the fungi and other microbes living on trees vary between the edges and center of forests. Because most forests contain many different tree species, it has been difficult to determine whether this microbial diversity results from the tree species themselves (the host organism) or from the varying environmental conditions at the interior versus the edge of the forest.

To answer this longstanding question, Zahn studied one of the most unique “forests” in the world, with his findings recently being published in Fungal Ecology.

The project focused on Pando in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest, the world’s largest tree.

While Pando looks like a forest covering 106 acres, it is actually a single clonal aspen made up of more than 40,000 genetically identical branches connected by a massive root system. This unique “forest” offered a rare opportunity to investigate the causes of microbial differences, since any variation in communities across Pando could only be attributed to environmental factors — such as wind, sunlight, or exposure to airborne spores — rather than genetic differences within the single host organism.

“Using DNA barcoding to build models of the fungal microbiome of Pando across its entire expanse, we showed, for the first time, that edge effects are real for microbes,” Zahn stated. “We also find that wind-blown environmental inputs shape microbiome assembly more strongly in small or fragmented forest patches. As deforestation increases, patchier landscapes increase microbiome variability, which can reduce plant resilience.”

Why William & Mary

While there are a number of universities with Ph.D. programs where Zahn could build his lab, he said it was the combination of a strong STEM program and the liberal arts that brought him to William & Mary.

“The School of Computing, Data Sciences & Physics has the rigorous focus on integrated science that my program needs, but it is rooted in an appreciation of the liberal arts,” explained Zahn. “Science is an inherently creative field, and I want to attract students with interdisciplinary interests.”

His lab’s use of AI to help predict high-dimensional microbiome dynamics to aid in conservation and restoration work is one example of the importance of an integrated approach. For this research to have real impact, he needs policy expertise, data scientists, public outreach, and practitioner support to actually implement the solutions on the ground.

To help find local partners to support his conservation projects, Zahn is part of W&M’s AI4Environment initiative, where he works with the Institute for Integrative Conservation.

“Making something happen in a research project is different from making it a standard practice that has a real effect on conservation efforts. I know that I will need help translating our applied research into actual interventions, and William & Mary is the place where people support that kind of interdisciplinary collaboration,” Zahn said.

Looking Forward

While still in the process of building his lab in ISC4, Zahn is working with VIMS faculty on two grant proposals focused on coastal restoration and microbiome engineering, and collaborates with universities around the world.

Zahn currently teaches “Supercomputing for Science,” where he shows students how to leverage William & Mary’s research computing infrastructure to tackle large-scale questions. He also hopes to develop a course in advanced statistics and data visualization, helping students turn complex data into clear, compelling stories.

He sees great potential in William & Mary undergraduates, many of whom pursue seemingly unusual double majors. Having started his own academic journey as a literature major before switching to biology, he believes interdisciplinary training prepares W&M graduates to make an impact.

“At the time, I didn’t even know what grad school was or what jobs were possible. It didn’t matter — I just wanted to know more. I see this same passion in William & Mary students. Their broad, well-rounded interests will be extremely useful in our rapidly-changing society.”